- Home

- About

- Training & Events

- 2027 Symposium

- Resources

- For Members

|

|

|

|

PWSR Toolkit Study PageWelcome to the “STUDY” section of the PWSR Toolkit. Partnership Wild and Scenic River (PWSR) studies evaluate and document eligibility, suitability, and support for river designation into the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Information on this page is geared for groups undertaking Congressionally authorized Wild and Scenic River (WSR) studies using the Partnership model that is used for rivers that flow through predominantly non-federally owned lands. This “Study Phase” follows the extensive organizing, outreach, and community engagement that was likely undertaken to get a Wild and Scenic River Study Bill introduced and passed by Congress (see the “Explore” page of the PWSR Toolkit for guidance on that earlier phase to authorize a PWSR Study). This STUDY section was developed to provide insights on what to expect, examples from other studies, and advice for undertaking a PWSR Study. It does not represent official guidance or legislatively mandated procedures for conducting a PWSR Study. Throughout this section, examples primarily from the York River Wild and Scenic River Study are provided, though others are noted as well. York River in southern Maine was one of three “partnership” rivers authorized for WSR studies by Congress in 2014, along with the Nashua River (Massachusetts and New Hampshire) and Wood-Pawcatuck River (Connecticut and Rhode Island) – both of which were designated into the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System in 2019. Examples are just that – details of an approach used to conduct a PWSR study in a manner that met the local needs and conditions. There is no optimal or standard way to conduct a PWSR study. The National Wild and Scenic Rivers System website, https://www.rivers.gov/, has extensive information (maps, publications, guidance, legislation) about WSRs and the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. Additional information on WSRs is available elsewhere on the RMS website – see the Wild and Scenic Rivers Resources section at https://www.river-management.org/wild-and-scenic, which includes a section on conducting WSR studies for rivers on federal lands, with federal agencies as the lead convenors of studies (though note that there are some key differences in the approach and requirements for PWSR studies as described throughout this PWSR Study section). Similarly the Wild and Scenic Rivers Coalition provides helpful information about protecting rivers through the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Program (see https://wildriverscoalition.org/how-to-protect-rivers-as-wild-and-scenic/), though its website resources are primarily focused on WSR designations on federal lands. After Congress passes and the President signs a Wild and Scenic River Study Bill into law, a Partnership Wild and Scenic River Study can begin. PWSR studies are locally led, that is, local groups or communities organize the approach, content, and execution of the study, often with assistance from state and regional experts involved with river conservation or river-related resource management. National Park Service (NPS) is the federal agency partner for all Congressionally authorized PWSR studies. NPS provides financial and technical assistance to complete the local study, and the agency is responsible for producing a summary report back to Congress on the suitability and eligibility of river designation, as well as a description of the approach and outcomes of the local study. The authorizing legislation for your PWSR study may stipulate certain provisions, such as specific river segments to study, issues or content areas to evaluate, or certain groups or jurisdictions to include. PWSR studies involve:

Partnership WSR studies require certain elements or products to meet suitability criteria for designation to demonstrate the local support and capacity to manage rivers:

Local PWSR studies typically last about three years, but many factors can affect the length of time needed to conduct and complete the overall study, including timing of funding awards, availability of information and data, additional data gathering efforts, town voting processes and formats, and local capacity. A separate National Park Service WSR Study Report is completed after the local study work is complete – typically at the conclusion of the local community vote process. The time it takes for NPS to prepare its Study Report, issue it for public comment, and deliver it to Congress can vary and is beyond the control of the local study group. Timing of key steps for some of the more recent PWSR studies and designations are shown below:

Funds for Congressionally authorized PWSR studies are provided through the National Park Service budget, as approved by Congress. To engage local communities and partners effectively, NPS typically funds the locally-based PWSR study process through a Cooperative Agreement with the coordinating entity or fiscal agent for the local study. Local watershed councils or river associations, or other local non-profit conservation organizations, usually serve as fiscal agents on behalf of the local study committee. Fiscal agents must have the capacity to accept, manage, and disburse federal funds; complete annual financial audits; and meet insurance requirements, as well as other certifications contained in federal forms SF424 and SF424B. From a practical standpoint, fiscal agents need to work efficiently with partners and jurisdictions across the full study area and should be willing and able to undertake efforts to secure and manage other funds (e.g., foundation funds, state grant awards, etc.) on behalf of the local study committee as needed. Cooperative Agreements (CAs) typically have a 5-year maximum term. Funds are awarded annually, with the initial execution of the CA and with subsequent CA modifications to add funding each year. Ultimately, these CA funds support development of both the local River Management Plan and the NPS Study Report. The three PWSR studies authorized in 2014 were initially approved for $184,000 each, with $64,000 awarded through the CA in the first year and $60,000 awarded in each of the second and third years through CA modifications, subject to passage of the federal budget each year. The primary use of funds is usually for staff that manage the study and coordinate the work of the local study committee. Funds can be used for study-related projects and services through subawards or contracts with other entities. Other uses of funds include special services (e.g., mapping, outreach, facilitation, website development); management plan development and printing; outreach materials; meeting supplies; administrative costs; and travel. Indirect costs for the fiscal agent are permitted.

Early planning and timely organizing will help your study get off to a successful start. A core group of the proponents that engaged communities and garnered support to pass your river Study Bill (see activities under the “Explore” section, if you’re not there yet!) usually are the key local organizers at the beginning of the Study phase. This core group will work closely with NPS and local communities in the interim period between Congressional approval for the study and formation of the local Study Committee. Some key aspects to consider or plan for when undertaking your study are noted in the sections below. PWSR study committees (or study teams) typically include appointed members from the jurisdictions through which the study river flows and/or jurisdictions identified in the study legislation and can include tribal, municipal, regional, county, and state interests. Often study committees will have advisors or associate members as a way to include and engage additional interests and expertise from agencies, community groups, academia, private sector, and nonprofits. The interim group will need to make presentations or conduct meetings with town governments to describe the river study and solicit candidates for the Study Committee. Town governments may want help from the interim planning group to identify candidates or to develop an application and selection process to aid in making appointments to the committee. There is likely to be some carryover of individuals that were previously involved in the Study Bill process, and there is a benefit to including those with knowledge of the history of the initiative. However, it’s possible that most appointees to your study committee will be “new” to the process.

Study committees typically have staff to coordinate and manage various aspects of the study. Staff tasks and responsibilities can vary based on the focus of the river study and involvement and expertise of the study committee members but generally include providing support and facilitation for meetings, subcommittee coordination, public outreach, event coordination, project management, partner engagement, study documentation, report writing, and overall development of the river management plan. Staff may be existing employees of the organization serving as fiscal agent/coordinator of the study or may be hired into a contract position. Some groups may hire multiple staff for different aspects of study implementation or contract for special services as needed (e.g., website development, GIS mapping, report design, etc.). In some cases, the NPS has hired a Study Coordinator directly when no fiscal agent has been willing or able to take on this responsibility.

The Study Committee will need to decide its operating procedures and structure very early in its establishment. This can be achieved through establishing bylaws, though often bylaws are not developed and adopted until after a river is designated, and the Study Committee has less formal operating procedures – but ones that are still agreed to and documented in the minutes. The interim committee may want to provide some preliminary guidance for consideration by the newly formed Study Committee. Committee member roles and terms, officers, meeting frequency and formats, decision-making procedures, voting rules, subcommittee establishment and operations, and budget reporting should all be agreed upon and documented. The Study Committee likely is required (and, if not, should strive) to adhere to municipal public meeting notice and public participation requirements. Recent PWSR Study Committees have formed subcommittees to focus on different aspects of the overall study. The Nashua and York PWSR studies each had two subcommittees: one to address outreach, communications, and public engagement; and one to focus on identifying “outstandingly remarkable values” and associated resource management issues. Similarly, the Wood-Pawcatuck had an Outreach Subcommittee, but instead of one ORV Subcommittee, it had four geographic-based subcommittees that focused on the subset of rivers in its sub-area and were tasked to, “research their local community information about ORV related information, develop a proposed classification for each segment in their sub-basin, and get a start on [identifying] known issues or opportunities to include in the management plan.” Creating an inclusive PWSR study process can lead to a more robust and thorough study of your river and communities. Aim to structure your study so that everyone has the opportunity to learn about the study, contribute perspectives and ideas, and participate. As the study committee is being formed and plans for the study are being developed, it’s a good time to find ways to involve more groups and individuals, particularly those who may be systematically underserved or underrepresented in community planning and natural resources management. NPS is working to improve equity and inclusion in all of its programs and processes, and it welcomes feedback on strategies, successes, and innovation. Below are some suggestions to improve equity and inclusion for PWSR studies.

River Network provides tools, training, and resources to promote equity, diversity, and inclusion in river protection efforts. River Network maintains a comprehensive Resource Library, and it developed a two-part toolkit to explore climate resiliency strategies and equitable engagement of communities in climate resilience work that provides insights and strategies relevant for river stewardship efforts.

An early focus on outreach can aid your study’s longer-term public engagement efforts. It’s helpful to have a website to direct people to basic information about the study, upcoming events, and how to be involved. A stand-alone website (i.e., a new, unique domain name with content solely for the purposes of the study) is ideal for a PWSR study, but sub-pages on an organization’s existing site can also work for the short term, as long as there’s a clear separation of the river study and other work undertaken by the organization. You’ll want to choose a domain name and format that will work for the study and also could be used post-designation. Websites from recent PWSR studies:

As a study progresses, the website can be the repository for study documents, committee meeting announcements and minutes, presentations / outreach materials, maps, and various background reports on river resources. Having a way for people to “sign up” on the website to receive future study announcements or updates by email is a good way to build your contact list. Your website can also direct viewers to any social media accounts for your study. Use of social media (YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, blogs, etc.) to support your study will likely depend on your committee’s or staff’s knowledge of various platforms and its capacity to sustain a social media presence. The level and details of “branding” a river study have varied. More extensive branding (including development of a study-specific logo) can be helpful if the PWSR Study is one of several initiatives your river or watershed association is currently undertaking – to clearly identify and differentiate the PWSR study from other river projects and activities. Branding considerations can be as simple as using consistent font, style, and color choices for study-specific letterhead, reports/documents, and outreach materials (presentations, banners, flyers, posters, etc.). Logos from recent PWSR studies (in both cases, an existing watershed organization with long-term river management and community engagement initiatives was the fiscal agent, lead organizer, and employer of staff for the study; a logo was not developed for the York River PWSR study):

As you develop web pages, outreach materials, social media content, and presentations, aim to make them “508 compliant” to maximize accessibility and usability for all, including individuals with disabilities. The U.S. General Services Administration’s Office of Government-wide Policy provides extensive guidance and technical assistance to improve accessibility: https://www.section508.gov/. Now’s a good time to review the questions and concerns about river designation that you heard when you were working to gain support for your river’s Study Bill. It’s likely that the same issues will be raised again now that the study is underway, and you’ll want to be able to respond. Common issues and questions from recent PWSR studies that you’ll likely encounter, if you haven’t already, could include:

Your Study Committee will want to review these types of questions and develop fact sheets or other outreach materials that fit your needs.

It’s important that your Study Committee provides ample opportunities for citizens to ask questions and share concerns about the study, river resources, and river designation. Your study will be strengthened by listening to and incorporating public input into your overall study process. Issues/concerns can be vetted and researched by your committee and be factored into its assessment of designation suitability. The Comprehensive River Management Plan you develop can document concerns, findings, existing conditions, and any solutions or management recommendations. Fear of federal government “overreach,” interference with local river and land use management, and concerns about private property rights tend to dominate worries about designation. In some more extreme cases, misinformation about the program and/or federal river management examples taken from non-PWSRs can create confusion – which means your committee will need to be prepared to provide objective, clear and consistent information about PWSR designation. PWSR designation does not result in federal government management of local river systems, changes to property rights, or changes to local ordinances and regulations. Locally-led river stewardship efforts are bolstered with the funding, technical assistance, collaboration, and community engagement that result from PWSR designation. The reality of what PWSR administration and implementation means is probably best demonstrated by the existing PWSRs (as of mid-2022, there were 16 PWSRs involving 140+ different towns). In all these cases, PWSR designation provides additional support for local river stewardship efforts without federal “takeover” of private property and river management or interference with local governance. Furthermore, designation legislation for PWSRs codifies the role of the National Park Service and the principles of local governance. Each time Congress adds a new river to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act is amended. Specific language written into the Act for each PWSR designation upholds the PWSR principles of local control, no federal takeover or management of private property, and river management that is consistent with the local Comprehensive River Management Plan. See a SUMMARY TABLE noting how and where “partnership” principles for recent and proposed PWSR designations are introduced in House Bill language and codified in Public Law. Here are examples of text excerpts and information contained in various communications to describe the federal agency’s role with management of designated PWSRs.

Section 7 of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act directs federal agencies to protect the free-flowing condition and other values of designated rivers and Congressionally authorized study rivers. Section 7 applies to water resources projects with work below the ordinary high water mark that are federally assisted (i.e., those that require a federal permit or use federal funds). Projects subject to Section 7 review can include restoration projects, bridge replacements, highway widening, riverbank stabilization, and other major infrastructure projects – if projects involve work “below ordinary high water” and use federal funds (grants, loans, etc.) or require a federal permit (Army Corps, etc.). Section 7 of the WSR Act applies only to specific federally assisted projects and does not impact local zoning and ordinances, land use of private landowners, state permits, or non-federally assisted river projects, which remain governed by local and state regulations regardless of designation. Ultimately Section 7 aims to safeguard the free-flowing nature of designated rivers as well as the specific ORVs that serve as the basis for designation from negative impacts of federal projects. Section 7 prevents licensing or exemption by FERC of new dams or hydropower facilities that would impact designated rivers. It prevents or limits federal projects which have a direct and adverse effect on, invade, or unreasonably diminish the free-flowing nature, outstandingly remarkable values, or water quality of the designated rivers. During a PWSR Study, Section 7 protections are applicable, though the review and evaluation criteria are slightly different for study rivers than for designated rivers. As the federal agency that administers PWSR designations and studies, NPS leads the Section 7 review and issues findings. Local committees (during the study phase or post-designation) can provide input to NPS on projects and river resources as part of the agency’s Section 7 review.

Additional information, implementation guidance, and helpful definitions for terms related to Section 7 are provided in the links below:

Some other topics or factors your Study Committee will want to consider early in your study process might include:

Some of the best advice to assist you in organizing and conducting your study can come from:

Research existing PWSRs with characteristics similar to your river: Is yours a coastal river? Do you have significant areas of state-owned lands along your river? Does your watershed span multiple states? Do you anticipate geologic features being one of your prominent ORVs? Is agriculture an important land use in your region? Are there working dams on some of your study rivers?

Talk to your NPS rep! They are a member of your study team and able to provide support and assistance in many ways. Chances are they’ve been directly involved in other PWSR studies, and they know the PWSR network and where to point you for specific assistance.

Specific eligibility and suitability criteria must be met for rivers to be eligible for designation into the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. To be eligible, rivers must be free-flowing and possess at least one river-related outstandingly remarkable value (ORV). A specific water quality threshold is not a criterion for eligibility. However, water quality is a value to be protected or enhanced for designated rivers, so it should be assessed and documented in your study. The suitability assessment for PWSR designation involves evaluating communities’ support and capacity for river protection. There must be strong local support, capacity, and cooperation for protecting the river’s ORVs, free flowing condition, and water quality, culminating in municipalities’ affirmative votes to pursue river designation and endorse the locally developed Comprehensive River Management Plan. NPS Reference Manual 46: Wild and Scenic Rivers (April 12, 2021), a guidance manual for NPS on implementing provisions of the WSR Act, includes information on eligibility criteria and assessments that is applicable for WSRs and PWSRs. Some relevant sections from Reference Manual 46 (RM46) are noted below. RM46 guidance on free-flowing condition: “Section 16(b) of the WSRA states: Free-flowing, as applied to any river or section of a river, means existing or flowing in natural condition without impoundment, diversion, straightening, riprapping, or other modification of the waterway. The existence, however, of low dams, diversion works, and other minor structures at the time any river is proposed for inclusion in the national wild and scenic rivers system shall not automatically bar its consideration for such inclusion: Provided, that this shall not be construed to authorize, intend, or encourage future construction of such structures within components of the national wild and scenic rivers system. When assessing free-flow, it is important to document the river’s in-channel condition and hydrologic function, any modifications of the waterway or banks, and how such modifications affect the river’s free-flowing condition. Rivers that have dams above, downstream, or on a tributary to the study segment, including those that regulate flow through the segment, along with the existence of minor dams, rip-rap, and other diversions within the segment, may still be eligible as long as the river is otherwise free-flowing and supports at least one ORV. River segments that do not meet these criteria are ineligible.” You want to be able to show where your river functions like a river and where it doesn’t. Identify dams, impoundments, diversions, hardened shorelines, and bridges and culverts, and describe implications for river flow when known. You might need to conduct a visual survey (or take field measurements of hardened shoreline, for example) in areas where you are lacking information, though a detailed hydrologic flow survey is not expected to be completed as part of your PWSR study. Where to look for information: state or town geospatial databases for road-stream crossings and river dams; state DOTs or other transportation agencies (they should have detailed information on shoreline alterations associated with bridges); dam owner reports to licensing agencies; local public works departments; shoreline surveys and other special studies conducted for your river or watershed (instream flow studies, fluvial geomorphological studies, culvert surveys, fish passage assessments); local knowledge, including historical societies for information on historic/remnant dams or mill structures. RM46 guidance on water quality: “… Along with a river’s free-flowing condition and ORVs, water quality is a third fundamental value that must be protected and enhanced on all WSRs. However, while water quality condition is a fundamental value of WSRs and has implications for classification, water quality is not an eligibility criterion.” WSRs generally have very good water quality conditions to support multiple uses and sustain healthy aquatic ecosystems. You will want to document existing water quality conditions, assessments, supported uses, and water quality management and monitoring programs in your study. Where to look for information: state water quality assessments, reports, and databases; state and EPA point source discharge permit programs; ongoing state and local water quality monitoring programs (beach sampling, shellfish sanitation surveys); state agencies’ nonpoint source pollution programs, river programs, and watershed assistance programs; volunteer sampling programs (water quality, aquatic macroinvertebrates); local stormwater management programs; shoreline surveys; local knowledge of conditions and other sampling programs. RM46 guidance on ORVs (underlines added): “Outstandingly remarkable values (ORVs) are defined as the characteristics that make a river worthy of designation. These are river-related or river-dependent values that are unique, rare, or exemplary at a regional or national scale of comparison. They can include scenery, recreation, geology, cultural, fish, wildlife, or other similar values such as ecology, hydrology, botany, or paleontology resources. In addition, rivers with exceptional water quality may sometimes include water quality as an ORV. Only one ORV is needed for a river to be considered eligible.

“…. The determination that a river contains ORVs is a professional judgement based on the [Interdisciplinary Team or Study Team] and objective, scientific analysis.” More information on ORVs:

It’s typical for a Study Committee to form a subcommittee that focuses on ORV identification and documentation. The subcommittee can engage additional resource experts, as needed, particularly for assistance with determining if a resource is unique, rare, or exemplary in a national or regional context. Where to start:

Existing assessments and designations by resource agencies are extremely helpful, but there can be data gaps and/or needs for re-assessment to confirm the current status of potential ORVs. Additional assessments, expert input, detailed analysis by your ORV team, or new studies might be needed to evaluate ORVs or water quality conditions for your PWSR study.

RM46 guidance on determining suitability for designation: [For WSR studies] “Design a suitability study to address the following:

“… For a partnership study river to be found suitable for designation, there must be strong evidence that local communities are willing to self-regulate, and to work cooperatively with agencies at all levels of government, along with residents and non-government organizations (NGOs), to permanently protect the river’s ORVs, water quality, and free-flowing condition.” For your suitability assessment, you’ll need to document and assess the existing management frameworks, protections, community capacity, and local support for ORVs and river conservation (including federal, state, and local regulatory and non-regulatory measures). The suitability evaluation for “strong evidence” of community support is more qualitative than the eligibility evaluation for ORVs and free flowing conditions. The ultimate indicator of suitability for PWSR designation will come at the end of your study (and after you’ve completed your suitability assessment and written your River Management Plan), when towns vote to endorse designation and the plan. Where to look for information/what to document or evaluate: town comprehensive plans / master plans and open space plans for river protection policies and priorities; local regulations, ordinances and zoning (including shoreland zoning); municipal staff capacity to implement programs or enforce rules; town boards and commissions and their roles for protecting ORVs and river resources; state programs and rules; federal programs and partners; local funding for river protection efforts; other local and regional river conservation/restoration initiatives, including work by nonprofit groups; local partnerships promoting sustainable river use and river protection; river initiatives that involve citizen volunteers; other river use, river management or ORV related plans (nonpoint source management plans, river use and access management, scenic resources inventories, etc.). Your committee will need to identify the specific rivers or river segments (identifying the upstream and downstream boundaries of each river segment, as appropriate) that meet eligibility criteria, plus assign a designation classification of wild, scenic, or recreational to the river segments you are proposing for designation. The WSR Act describes each class of rivers as follows:

RM46 guidance on determining classification: “When a river is found eligible for WSR designation, it is assigned a preliminary river classification as wild, scenic, or recreational. Classification is based on the existence of water resource projects in the corridor, the level of shoreline development, accessibility to the river, and water quality at the time of designation. A river’s preliminary classification is not indicative of the outstandingly remarkable values for which a river might be added to the NWSRS. For example, a scenic river segment need not possess outstanding scenery, and a recreational river segment need not have recreation identified as an outstandingly remarkable value.” “The four criteria used in determining classification are 1) presence of water resource development, 2) shoreline development, 3) accessibility, and 4) water quality.” The data and information you compiled for your assessments of free flow condition (including riverbank alterations, impoundments, diversions, etc.) and water quality, plus assessing the level of development in adjacent shoreline areas, can help your committee determine the most accurate classification(s). You can assign different classifications to each river segment, based on the characteristics of each segment. One classification is not more desirable than another, i.e., a “wild river” is not more worthy of designation than a “recreational river.” The classification is intended to accurately characterize the river’s current status and serve as a baseline to provide a framework for future management strategies to sustain river qualities. This process will be coordinated closely with NPS staff, as they must formally recommend segments and classifications to Congress. For PWSRs, the local “Comprehensive River Management Plan” (a WSR Act term) developed during the study serves as the guide for implementation when the river is designated. The plan identifies stewardship, outreach, protection and/or restoration measures to sustain your river’s outstandingly remarkable values (ORVs) for current and future generations. Unlike the plans developed for WSRs designated on federal lands, a Comprehensive River Management Plan is completed for PWSR studies prior to river designation as a part of the Study process. Even if a river is not designated into the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System, the plan still has value and can be implemented by communities and local partners. Coordination with NPS staff can ensure the plan meets PWSR study requirements, however the plan should be first and foremost an expression of the local vision for protecting the river. Plans can be river focused or watershed focused and can have any title that the local study committee chooses. The plan should describe your overall river study, including your approach, findings, and recommendations. How you organize your plan is up to your committee. Providing documentation for all ORVs and summarizing all existing protections for river resources can be cumbersome and you’ll need to find a balance in the level of detail you provide in the plan, while still adequately documenting eligibility and suitability findings. Make use of links to summaries of other reports, develop a detailed reference section, put lengthy tables and assessments in your appendices, and list separate volumes when you can.

More information, examples, and links to river management plans are provided in the sections below. River management plans developed for the most recent PWSR studies are listed and linked below. A quick look at the tables of contents will show you how plans are organized.

A deep dive into plans developed for prior PWSR studies will demonstrate various approaches to document eligibility and suitability findings within the river management plan. Details on some of the documentation for York River are noted below:

Suitability documentation: Some examples that demonstrated local support and capacity for river protection were included in the York River Watershed Stewardship Plan:

These and other specific examples were included in different sections of the Stewardship Plan. Summary tables of some town ordinances were included as appendices to the Stewardship Plan. A separate volume that provided a more thorough inventory and review of towns’ regulatory and non-regulatory approaches for river resource conservation was listed as a companion report since it was too lengthy to include in the Stewardship Plan. Your plan should address specific river issues, existing uses and conditions, and management considerations that are important to your communities, especially those related to any designation recommendations. Identifying and/or clarifying any issues in the plan can make implementation more straight-forward and can help alleviate concerns or uncertainties going forward. Two examples from recent PWSR studies are noted below:

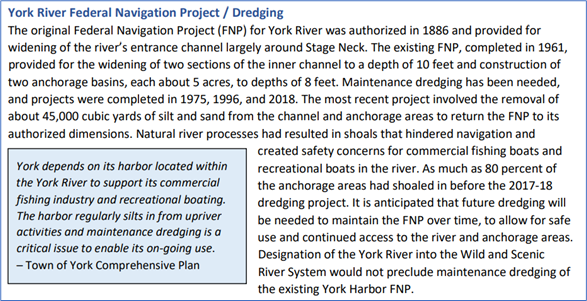

York River, ME – addressing existing uses / harbor dredging (a federally-assisted project) and compatibility with designation. Continued use of and access to York Harbor is very important to local commercial fisherman and recreational boaters, and periodic dredging is required to maintain access. The dredged area is adjacent to (just downstream of) the section of York River proposed for designation and would be subject to Section 7 project review by NPS. In its Stewardship Plan, the Study Committee described and documented baseline conditions/history of the Federal Navigation Project, local support, and the need for future maintenance dredging (see excerpted language below), and the Committee included a specific recommendation to, “Continue to support and implement maintenance dredges” in the Stewardship Objectives / Key Actions section of the plan.

Amendments to the WSR Act to designate PWSRs into the national system include language codifying the local plan as the Comprehensive River Management Plan required for all WSRs. Close coordination with NPS staff throughout the process will ensure that the NPS Report to Congress specifically recommends and endorses the local plan as meeting the needs of the Wild and Scenic River designation. This is demonstrated in the excerpts from the authorizing legislation for designation of the Missisquoi and Trout Rivers (Public Law 113-291): P.L. 113-291. SEC. 3072(b)(1) MANAGEMENT. (A) IN GENERAL. The river segments designated by paragraph (212) of section 3(a) of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (16 U.S.C. 1274(a)) shall be managed in accordance with (i) the Upper Missisquoi and Trout Rivers Management Plan developed during the study described in section 5(b)(19) of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (16 U.S.C. 1276(b)(19)) (referred to in this subsection as the ‘‘management plan’’); and (ii) such amendments to the management plan as the Secretary of the Interior determines are consistent with this section and as are approved by the Upper Missisquoi and Trout Rivers Wild and Scenic Committee (referred to in this subsection as the ‘‘Committee’’). (B) COMPREHENSIVE MANAGEMENT PLAN. The management plan, as finalized in March 2013, and as amended, shall be considered to satisfy the requirements for a comprehensive management plan pursuant to section 3(d) of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (16 U.S.C. 1274(d)). Your committee is responsible for development and production of the Comprehensive River Management Plan, including writing, design/layout, printing, and distribution. Funds awarded for your study through the Cooperative Agreement should be budgeted by your committee and used to cover all productions costs, including staff costs and any contractual services. Your decisions for plan organization, layout, and design should account for usability and readability for both print and digital formats. If printed copies of your plan won’t include all appendices, maps, or other content, be sure to note in the printed version how and where to access this information. Digital copies of your plan should be 508 compliant (see https://www.section508.gov/create/ for helpful guidance, particularly for creating Word documents and PDFs that are accessible).

Public involvement throughout the study is a key part of all PSWR studies and is one of the most important functions of the local study committee. Your study will likely have multiple public engagement and communications objectives – to inform people of the study, PWSRs and designation benefits; to get public input on ORVs and river use issues; to improve awareness of and connections to river resources; and to gauge and build support for river protection efforts, including PWSR designation. As such, you will need a multifaceted outreach approach involving a wide range of activities (e.g., meetings, workshops, presentations, public input forums/listening sessions, river paddles, walking tours, river clean-ups, tabling at festivals, photo contests, hands-on science projects, riverside art events, targeted mailings, etc.) and diverse products and materials (press releases, newsletters, Story Maps, social media, print materials, website, videos, PSAs, posters, displays for events, PowerPoint presentations, interactive maps, flyers, postcards, letters, etc.). Establishing a relationship with the media can be very helpful to reach additional audiences – for the York River PWSR study, local media wrote and published more than 40 stories over the course of the study. As part of the documentation in its PWSR study reports, NPS describes the outreach and stakeholder engagement conducted for each study. Outreach examples are included in appendices for recent study reports:

The examples below highlight some different types of outreach products used in communications and to promote public engagement events.

Local support is a key part of PWSR studies and is necessary to move a PWSR designation forward. The demonstration of local endorsement is two-fold and includes: approval to pursue designation into the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System and acceptance of the river management plan that establishes stewardship objectives and recommendations to sustain river resources. Affirmative votes / approvals by the legislative bodies of each municipality demonstrate suitability for PWSR designation. If a municipality does not approve designation and the plan, its river segment(s) will likely be deemed unsuitable for designation in the NPS Report to Congress. Your Study Committee will be the first entity to endorse pursuing designation and adopt the river management plan. If the Study Committee does not approve pursuing designation, then subsequent town votes aren’t needed. Your Study Committee’s votes / approvals could be at different times and will need to be recorded in minutes of meetings. [For example, the York River Study Committee voted to endorse pursuing designation for at least a part of York River and its major tributaries and voted to establish the recreational classification for any designated segments at its October 2017 meeting; voted to approve specific river segments for the designation proposal at its November 2017 meeting; and voted to approve the York River Watershed Stewardship Plan at its July 2018 meeting.] Each town’s legislative or governing body will be asked to vote to endorse river designation and the river management plan. Formats of endorsement votes vary by town and can include, among others:

Depending on the municipalities involved, votes for your study can be the same format in all communities (e.g., select boards and councils in all 12 towns in the Wood-Pawcatuck River study area voted on resolutions) or you might have different vote formats by town (e.g., citizens in two towns voted on ballot items, and town councils in two towns voted on resolutions for the York River study). Check with your towns’ managers, clerks and/or councilors well in advance of any votes to confirm the format and timing. Offer to assist with drafting or reviewing language for any articles or resolutions that will be voted upon. Following the municipal votes or approvals, regardless of format, you’ll need official documentation (typically from a town clerk) that records the local approval or voting results. It’s likely this documentation will be incorporated into the NPS WSR Study Report that will be developed for your study. See the NPS WSR Study Reports (appendices) for the Nashua River and York River studies for examples of documentation of town approvals/votes. The legislative bodies in each town must vote as part of the suitability determination for PWSRs. It’s optional to obtain additional approvals or support from other town boards and committees. You can choose to request that other town boards (e.g., town conservation commissions, planning boards, historic district commissions, harbor boards, etc.) endorse designation, and you’ll have to work with each to determine whether it’s possible and how that support is best demonstrated and conveyed. Missisquoi and Trout Rivers, VT – article for town meeting: To see if the voters of the Town of _______ will petition the Congress of the United States of America that the upper Missisquoi and Trout Rivers be designated as Wild and Scenic Rivers with the understanding that such designation would be based on the locally-developed rivers Management Plan and would not involve federal acquisition or management of lands. Wood-Pawcatuck Rivers, CT & RI – resolution for council consideration: BE IT RESOLVED, that the Town of ______ hereby supports the recommendation for designation of Seven Rivers of the Wood-Pawcatuck Watershed – Beaver, Chipuxet, Green Fall, Pawcatuck, Queen, Shunock, and Wood Rivers – as Wild and Scenic Rivers through an act of the United States Congress. And, BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED; that the _______ Town Council endorses the Wood-Pawcatuck Wild and Scenic Rivers Stewardship Plan developed by the Wood-Pawcatuck Wild and Scenic Rivers Study Committee. York River, ME – ballot article and accompanying statement of fact: ARTICLE TWO: Shall the Town endorse the York River Study Committee’s recommendation to seek Wild and Scenic River designation for the York River and its major tributaries with the understanding that designation would not involve National Park Service ownership or management of lands, and further, accept the committee’s York River Watershed Stewardship Plan? Statement of Fact: The York River Wild and Scenic Study, which was authorized by the US Congress, evaluated the York River for inclusion in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System under its “Partnership” river model. The York River Study Committee believes a Partnership Wild and Scenic River designation would provide key financial resources, technical assistance, and a local structure to best enable implementation of the York River Watershed Stewardship Plan. The Stewardship Plan is a non-regulatory guidance document that recommends strategies to preserve important historic, cultural, economic and natural resources in the York River watershed consistent with goals in towns’ comprehensive plans. Community support for designation and acceptance of the Stewardship Plan is a prerequisite to Partnership Wild and Scenic River designation. However, such endorsement does not commit the Town to provide any financial resources. Funding to implement the Stewardship Plan is anticipated to come from annual Congressional appropriations through the National Park Service’s Partnership Wild and Scenic Rivers Program if the York River is designated. There is no land ownership or management by the National Park Service, and there are no required changes to local ordinances with a Partnership Wild and Scenic River designation. At various stages of the study process, it’s helpful to have letters of support to publicly demonstrate local endorsement of the overall study or, more specifically, the committee’s recommendation to seek PWSR designation – from individuals, conservation organizations, agencies, volunteer committees, etc. Letters can be sought in advance of town votes, for inclusion the NPS WSR Study Report, and/or to support Congressional efforts to sponsor and pass a river designation bill. Letters of support from river user groups and from organizations and entities that participated in the study and have a role in river stewardship initiatives are particularly helpful. Letters of support are a specific example that NPS can cite in its assessment of local support for river protection (a suitability criterion). Details of support letters contained in two NPS WSR Study Reports are noted below:

In most cases, communities have endorsed river designations usually with overwhelming support. However, there are instances of towns voting down designation or deciding to defer decisions to a later time. Outcomes of votes will affect the suitability assessment for PWSR designation. If a town does not support designation, its river segments will not be suitable for designation. Another factor to consider is that not all towns identified and participating in the study will necessarily be voting at the conclusion of the study. The need for community endorsements through votes will be based on the eligibility and suitability findings, the river segments recommended for designation, and river management approaches identified in your plan. Merrimack River, NH – lacked local support, deemed not suitable. A study of the Upper Merrimack River found it met eligibility criteria for a PWSR designation for river segments flowing through five municipalities. In May 1994, four towns voted against seeking designation and a fifth town’s Council tabled its vote. Without the affirmative local votes, the river was found not suitable for PWSR designation and a recommendation against pursuing designation was made by NPS in its Study Report. Lamprey River, NH – deferred vote in one town, two rounds of designations by Congress. In May 1995 at the conclusion of the river study, three of the four study area towns voted overwhelmingly to pursue designation; the fourth town deferred its decision and did not take a vote at the time. The river segments in the three towns that voted were designated by Congress in 1996. Four years later, the remaining community voted to endorse designation and 12 more river miles were added to the designation in 2000, through a second act of Congress. Musconetcong River, NJ – rejection by one township with later reconsideration and adoption, designation of additional segment by Secretary of the Interior. Resolutions of support for the management plan and designation were adopted by 13 of 14 river corridor municipalities in 2002, thereby demonstrating local support for two of three river segments eligible for designation. Congress designated those segments in 2006 under Public Law 109-452, and Section 5(d) authorized the Secretary of the Interior to add the additional segment upon a finding that there is adequate local support for designation and upon publication of notice in the Federal Register. In 2018, the Pohatcong Township Council reconsidered and voted unanimously by resolution to demonstrate its support for adding the additional segment, and the Secretary of the Interior published notice in the Federal Register on June 3, 2022. Missisquoi and Trout Rivers, VT – one “No” vote, designation recommendation adjusted. One of nine towns/villages considering designation voted down the article at its Town Meeting in 2013. The designation recommendation, and ultimately the segments identified in the 2014 authorizing legislation, was adjusted to exclude the 3.8-mile river section in Lowell (it happened to be an uppermost/headwaters river segment). House Bill H.R. 2569 as introduced would have allowed designation of the Lowell segment upon determination by the Secretary of the Interior of adequate local support for designation, but this language did not survive the legislative markup process. As noted in the NPS WSR Study Report, the town of Lowell can reconsider and should an affirmative vote occur, that section could then become suitable for PWSR designation. However, a second act of Congress would be necessary for designation. Missisquoi and Trout Rivers, VT – no proposed segments, no town vote. The study area included rivers in the town of Jay (along with nine other towns/villages), and the study committee included representation from all study area towns. Several major tributaries were evaluated and found to be eligible for designation, however, no suitability analyses were completed for the major tributaries. As noted in the NPS Study Report, “The Missisquoi and Trout River tributaries were not evaluated for suitability based on a desire to move forward with designation of the mainstem of the Rivers, and timing constraints on the Study.” The town of Jay contained tributaries only, so it did not contain river segments proposed for designation (having not met eligibility and suitability criteria), and townspeople were not presented with an article to consider at Town Meeting when all other study area towns were. York River, ME – no proposed segments, still conducted town vote. South Berwick is one of four towns with lands and water resources in the York River watershed, though no major tributaries and no river segments proposed for designation exist within the town. However, in conducting its PWSR study and in developing key actions for the York River Watershed Stewardship Plan, the Study Committee recognized the importance of implementing a watershed-based approach to preserve water quality, ORVs, and regional biodiversity. As such, the committee decided to seek endorsement from all watershed towns, and the South Berwick Town Council was asked to approve a resolution to seek designation and accept the Stewardship Plan. The Council approved the resolution by unanimous vote.

Earlier studies included an Environmental Assessment as part of the NPS Study Report to comply with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in evaluating alternatives and impacts associated with designation. More recently, NPS has concluded that PWSR Study Reports are consistent with NEPA Categorical Exclusion 3.2R, and environmental assessments are not required as part of its study process and reporting. The NPS regional environmental coordinator can provide current information on the appropriate NEPA process and required documentation. NPS WSR Study Reports for recent PWSR studies:

NPS allows the public to review and comment on its WSR Study Report and will post the report and other supporting documentation on its Planning, Environment, and Public Comment (PEPC) website, https://parkplanning.nps.gov. WSR Study Reports have a 90-day period for public comment, after which NPS will review and analyze comments received, if applicable.

If your study demonstrated eligibility and suitability for a PWSR designation (including affirmative local votes), a bill will need to be introduced and passed by Congress to achieve designation into the national system. Designation bills can be introduced by sponsors in Congress before or after NPS completes its WSR Study Report for your river study. It's important to keep your full Congressional delegation involved in and informed of your study as it progresses. At the conclusion of your local study, you will want your delegation to sponsor designation bills in the House and Senate. Invite your Congressional representatives to attend your public meetings and events and offer to meet with staff at their regional offices to provide updates periodically. If members of your delegation were not involved with the Study Bill for your river, you’ll need to spend more time describing the PWSR program and WSR designation, as well as your river’s resources and local support for PWSR designation. River designation bills introduced in Congress for recent PWSR designations are listed in this TABLE. If bills don’t pass within the 2-year session when introduced, bill sponsors will need to reintroduce bills in the subsequent Congressional session. The status and progress of bills that have been introduced can be tracked online on Congress.gov, including assignments to committees, hearings, committee reports, amendments, and other actions. PWSR designation bills are assigned to House and Senate subcommittees that will typically schedule hearings on the bills. Bill sponsors and National Park Service representatives will provide testimony on the bills at hearings, and often a representative of the local study committee is asked to provide testimony as well. Testimony can be provided in person, via videoconference, or submitted in writing, depending on the format of the hearing (see an EXAMPLE OF TESTIMONY given during a Senate subcommittee hearing on the York River designation bill in 2021 – this was read during a hearing videoconference, with written testimony submitted in advance). Subcommittee members have the opportunity to ask questions of those providing testimony at the hearings. Some links and resources that are included elsewhere on the STUDY page are listed again: National Wild and Scenic Rivers System website: www.rivers.gov, managed by the Interagency Wild and Scenic Rivers Coordinating Council (IWSRCC) National Rivers Inventory (NRI): https://www.nps.gov/maps/full.html?mapId=8adbe798-0d7e-40fb-bd48-225513d64977 Interactive NPS Story Map for the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System: https://nps.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=ba6debd907c7431ea765071e9502d5ac# The Wild and Scenic Study Process (December 1999), an IWSRCC technical report: https://www.rivers.gov/documents/study-process.pdf Wild & Scenic Rivers Act: Section 7 (October 2004), an IWSRCC technical report: https://www.rivers.gov/documents/section-7.pdf IWSRCC’s Section 7 Flowchart (October 2017): https://www.rivers.gov/documents/section7/section-7-flowchart.pdf NPS Reference Manual 46: Wild and Scenic Rivers (April 2021), a guidance manual for NPS on implementing provisions of the WSR Act: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/policy/upload/RM-46_04-12-2021-2.pdf RMS River Training Channel (includes a WSRs training series): https://www.gotostage.com/channel/93f4eecaee1d443eb2affdf20b34b594 River Network’s Resource Library - equity, diversity, inclusion and justice resources: https://www.rivernetwork.org/resource/equity-diversity-inclusion-resources/ U.S. General Services Administration Office of Government-wide Policy (accessibility): https://www.section508.gov/ NPS web page on PWSRs with links to websites for the 16 PWSRs: https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1912/partnership-wild-and-scenic-rivers.htm PWSR News page with information on events, program updates, and past newsletters: https://www.river-management.org/pwsr-news River management plans developed for recent PWSR studies:

NPS Planning, Environment, and Public Comment (PEPC) website: https://parkplanning.nps.gov, and PEPC project pages for recent PWSR studies, with links to NPS WSR Study Reports:

|

River Management Society

P.O. Box 5750

Takoma Park, Maryland (MD) 20913-5750

(301) 585-4677

[email protected]

© Copyright 2017, River Management Society